"Woodiss is Willing" by Henry Woodiss

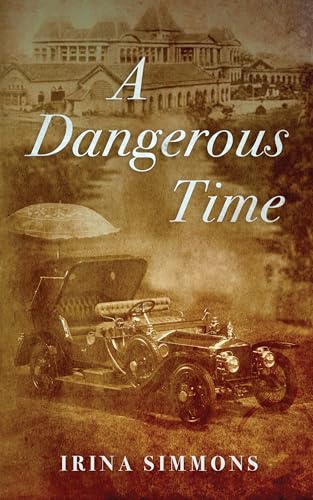

Immediately when you start reading this book, it gives the impression of being a lot of fun – humorous, cheeky and entertaining, and straight away the author (who, confusingly, is not the editor who wrote the alluring foreword), displays a great degree of good, old-fashioned English sense of humour, from a time before it perished at the hands of political correctness; and this is very welcome. The first quarter of the book reads like a “Carry On…” movie with a modern-day 18-certificate. It is satisfyingly explicit, holds nothing back, and promises a lot. Sadly, though, “Woodiss is Willing” does not continue in this vein. As for the sequel, I cannot say – I will be reviewing this next.

This is the first in a trilogy of autobiographical books about the life of Henry Woodiss – a simple gamekeeper who, thanks to his affair with the wife of an aristocratic friend, and her ensuing pregnancy, finds himself marrying into the upper classes and inheriting an enviable lifestyle – dusted off and edited by George Dalrymple. Although I have been asked to review this and its sequel, I can presently only comment on “Woodiss is Willing” as a stand-alone book.

Despite the persistent humour and humility of the uncomplicated, archetypical Yorkshireman Woodiss, and a string of belly laughs (including some tinged by cynicism), there is an underlying sadness about it all. The social class vulnerability that Woodiss implies to justify his moral ambiguity does not ring true, although his simplicity perhaps does – there is an innocence to Woodiss which can only be characterized by the rural folk of early 20th century England.

The book was written many years past (when exactly is not entirely clear, although it was clearly written in hindsight), and the author is long gone. The book has not been particularly well edited; it is likely that George Dalrymple was keen to retain the warts’n’all writing voice of Woodiss - but while amusing and engaging, with a great sense of humour, Woodiss is not a particularly eloquent author. His tongue takes a little getting used to, and at first is supposed as poor grammar which needs editing; however, once the reader can adjust to the northern monologue of the entire book, it becomes much easier to get into. That said, I feel the book would perhaps benefit from an editorial once-over, just to polish up the punctuation and if not the writing – the formatting, also, can be a little distracting.

In fact, this book offers a fascinating, fly-on-the-wall insight into a time and a culture that none of us will ever experience – it is both eye-opening and grin-inducing. It’s great to get a slice of genuine life from ‘twixt-wars Britain, told from the simultaneous point of view of two opposing classes of the time, in native tongue, rather than some PC-diluted fabrication of it; this book revels in colonial pomp and inequality, and its acceptance across the classes at the time.

The story becomes incredibly poignant, and devastatingly moving, to an extent that it actually takes you by surprise how sad it becomes - I liked this element of the book very much. The whole tale of Henry’s relationship with Edith, from dirty lust to full-blown love and friendship, is lovely to witness. At times, you do find Henry’s fake callousness and northern front a little annoying, but the tragedy, when it comes, is heartbreaking and wonderfully written. It is perhaps ruined by a light-hearted parting comment about Henry’s philandering to come in book two, which seemed a little out of place – I would have liked to have taken the feeling of tragedy into book two, and would prefer mention of Henry’s imminent conquests to have been omitted.

Also out of place, I felt, was almost the entire second quarter of the book, which confusingly altered the timeline, and brought events up to a much later date in Henry’s life – I felt this whole section was inappropriate for this instalment of the trilogy, and the book would have benefitted if this whole section (some 10,000 words or so), had actually been left out and retained for the second book. This section seems to have been included for little reason other than to address a later moment in Henry’s life, against the terrifying backdrop of imminent Nazi invasion, and the public distrust of Henry, wounded and unable to join his brothers on the battlefield. There is a huge amount of banter in this section (as in the book on the whole), characterized by typically northern humour, comprising long conversations about mundane topics (like bacon), and the last-word/endless retort mentality of Henry does become irritating, often long after the conversation has served its purpose to the reader. The dialogue is relentless – perhaps too much of it – and can get a little overwhelming.

Still, this is a thoroughly readable book, and Henry is utterly engaging. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind my saying that the book is a love affair with rural Yorkshire, but a realistically cynical one, marred by its ugly 19th century industrialization – this observation of drabness seems to increase with Henry’s age.

I look forward to reading the second instalment of Woodiss’s life:

“Woodiss Waits”.

BUY IT NOW FROM AMAZON >

In : Book Reviews

Tags: henry-woodiss george-dalrymple british yorkshire rural comedy fiction war