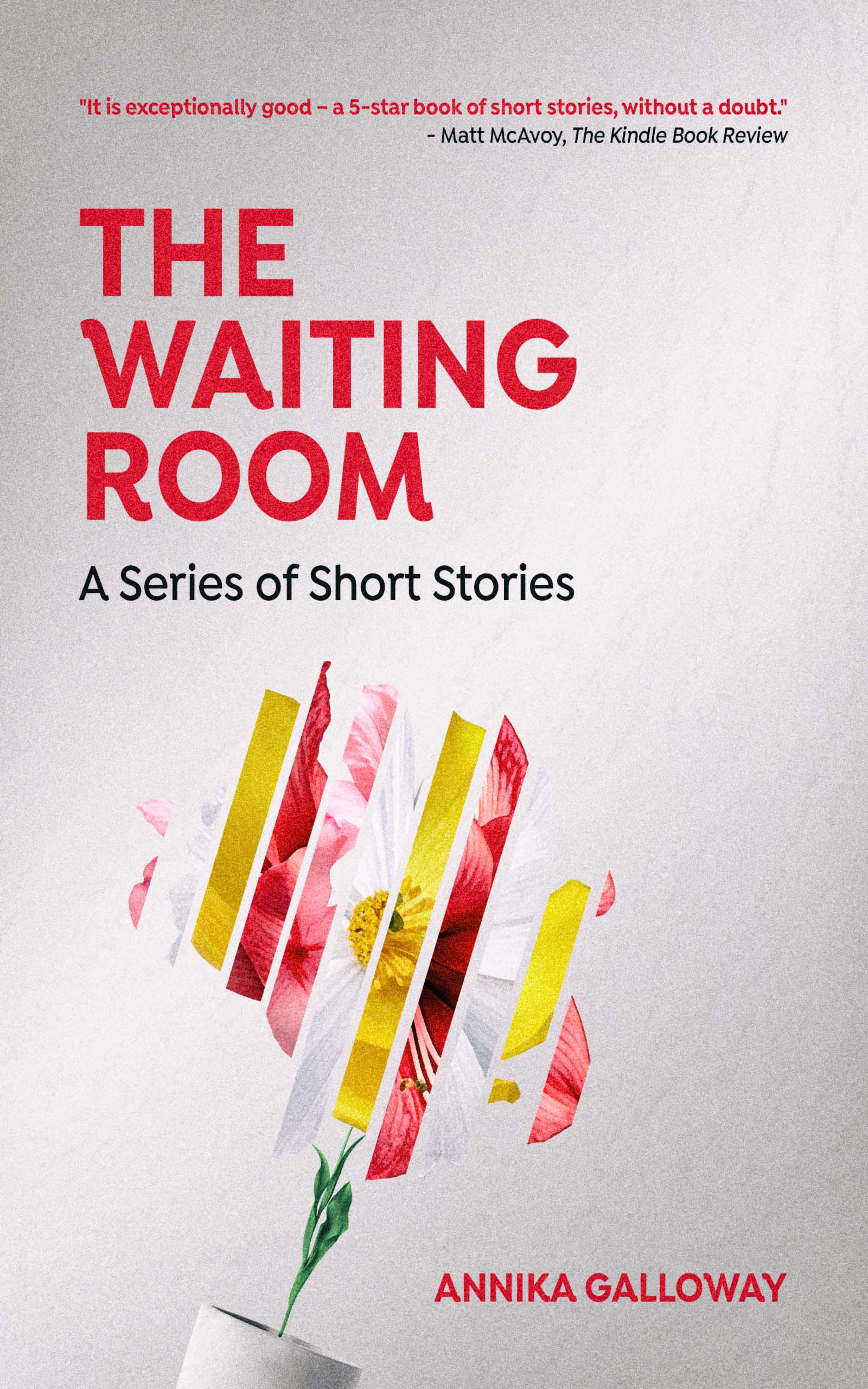

FREE SAMPLE OF MY NOVELLA "THE BLACK LINE"

Posted by Matt McAvoy on Thursday, August 21, 2014 Under: My Work

.jpg)

SUNDAY 7.50pm

ENFIELD UNDERGROUND STATION

“It's not even black,” remarks one amongst the crowd, without displaying the slightest hint of irony, “it's purple.” Those within earshot shoot ridiculing glances at the evidently dimwitted youth; someone calls him a “muppet”. He runs his finger defiantly along the newest colourful addition to Beck's iconic diagram of the tube network, emphasizing his wisdom.

The crowd is varying in content; some jovial, absorbing the atmosphere as if it is almost carnival-like, some less so, angry, furious even. And in their midst, a small element is terrified.

Some of the crowd hold banners, some hold candles. They scream and shout contrary protests – London's diversity of mind and character epitomized in one limited location. “Close the Black Line,” a section shouts; shouting in counter, a sub-group of black and Asian men and women (mainly the men – most of the women appear to be white and middle-class) shout back: “Racists!” Conflict simmers beneath the surface, threatening continuously to spill over into violence, but, on this occasion, never quite doing so.

Union members are here, perhaps loudest of all, their leaders too – one holds a placard crudely painted with the menacing warning: “R2D2 TOOK MY JOB – YOU'RE NEXT!”

Of those demanding the new line's closure, many wear black t-shirts, specially printed for the occasion, depicting a crucifix tombstone crossed out by a diagonal line, overlooked by three smiling cartoon £ signs.

They direct their protest through the fencing partitioning the world from the overground southbound platform at Enfield Station. Underground employees prevent their access into the station property itself, and the adjoining car-park is as close as they are permitted.

Amongst the crowd, a dark, sinister minority – a collection of three, two elderly men and a woman. A small number, but their presence no less tangible, and certainly not a little chilling. A dark atmosphere permeates the crowd, subtly, underlying, and it emanates from here, from this very group, slowly seeping into the crowd and its surroundings, like an odourless toxic vapour. The woman and one of the men speak quietly, monotonously, incoherently amongst themselves. The other in their group directs his attention elsewhere. He wears a long white beard and very long hair, and a long dark dirty coat with a black hooded top underneath. He too speaks, but not to his companions – he stares through the fence transfixed, quietly uttering to one particular individual - the man of power on the platform, who has yet to acknowledge him.

“The graves of St. Peter's charge have been stirred,” the man utters as though entranced; “the spirits must not be released.” The man's message is undoubtedly a warning of stark gravity – his demeanour and delivery of it, however, defies this – it is as though hopelessness has triumphed, and the man already feels defeated, that his warning has come far too late.

The target of his menacing vitriol, the man on the platform, is the flamboyant, eccentric and jolly Mayor Boris, flanked by two silent associates who look like accountants but probably aren't. He jokes and laughs as he always does when graced with the presence of a television camera.

Small crews from a limited number of selected channels have been permitted access to the platform – one has even been chosen to accompany the mayor onto the train, which patiently awaits his patronage, its doors expectantly open.

One news-crew, perhaps more shrewdly, is infiltrating the crowd outside, the young suit-attired broadcaster spearheading the crew approaching individuals who talk willingly, gleefully, and some passionately, into his hand-held microphone.

Mayor Boris astutely notices the excitement the crowd has stirred amongst the representatives of the media, and the way many of the cameras beside him on the platform have turned away to film the mass of people through the iron fence, recording their ire, amongst other things. This is okay – he does not demand attention overtly, but addresses each camera one at a time, in his own inimitable, charming and endearing way, eager to ensure that each present has the impartial benefit of his own viewpoint on the launch of the Tower line.

And why shouldn't he revel in his credit? He personally worked extremely hard to ensure the dream became a vision, the vision a goal, and the goal a reality. Made many sacrifices in the process – looking around at the sheer scale of opposition, for the first time an element of doubt creeps into his mind and he thinks it may have been one sacrifice too many. But, ever the eternal optimist, he persuades himself that these doubts are not new to him – success would prevail, and, as always, would win over the crowd.

From the corner of his eye he sees the dull yet penetrating glare of the long-bearded man, but ignores it, still smiling. In his peripheral vision he sees the old man's lips move, may even hear his words, but, were this the case, chooses to ignore them.

The dim youth was right – the Tower line isn't black; on Beck's map it is purple, a much lighter, more flowery shade than that denoting the Metropolitan line. This is Mayor Boris's vote-winning flagship policy, his legacy, and surely his re-election guarantee - a line long awaited on the Underground network; Enfield at one end and Croydon at the other, serving all the major towns in between which for too long have been denied the luxury, the sheer right to a quick and reliable tube transport network link, long enjoyed and taken for granted by the rest of the capital. Tottenham, Hackney, Peckham; so long were these areas marginalized and deprived of this benefit – overlooked and under-invested because, it is argued, they are poor areas, underclass areas, black areas.

“The term 'Black Line' is a racist one used by uneducated people because it runs through 'black' areas,” a young middle-eastern man explains angrily into the nearest television camera.

Nearby, some students shout: “That's not true,” while other students, which one could be forgiven for mistaking to be part of the same crowd, shout their agreement with the man.

“Londoners don't want to cough up for us,” he continues. “They've already got their tube. They would rather keep their Oyster fares down and see their council tax spent on flower beds and bin collections than invest in our further integration.”

“Rubbish,” someone shouts. Whether he intended the pun or not, a few people laugh. This riles the angry man further.

“This marginalization and contempt of our areas is blatantly obvious in the term 'Black Line'. This is why people don't want it – to keep blacks and Muslims in our place in the East End.”

“Who said the East End was your place?” someone shouts, but, perhaps fortunately, his voice is lost in the cries of protest from the students. This isn't going well for them – students are not prepared to be branded 'racist', despite their own frequent use of this tar-brush.

“That's not true,” blurts a pretty, fresh-faced girl amongst their group, initially almost apologetic and hurt by the misunderstanding, though this gives way to excitement as the same camera turns to face her, and she is afforded the opportunity to share the conviction of her cause. She herself wears one of the black t-shirts with the £ signs, and stretches its motif out to show the world. “We are protesting about the extension of Tower Hill station and the desecration of graves at St. Peter ad Vincula to accommodate it – that's why we're here, and why we're opposed to the Tower line.” Her associates shout and cheer encouragingly.

“So why are you calling it the 'black line'?” shouts the man.

“I didn't.”

“Maybe not you, but everyone else.”

A young man in the crowd interjects: “It's just a nickname.”

“Because it's a 'black' day,” another shouts. Then again: “It's a black day.” Then again and again until someone listens, which nobody does.

Shouting and bickering escalates between the two parties, again teetering falsely on the brink of violence, but not falling, not yet.

The broadcaster revels, placing himself directly between the camera and the crowd, sensationally though perhaps misleadingly focusing on the “incredible scenes of protest marring the launch of the mayor's new Tower line”.

Mayor Boris feigns indifference at the scenes of unrest, presenting himself professionally and in celebratory mood to the news crews.

“I am delighted to be among the first to experience riding these new trains.” So upper-crust, so posh, he immediately draws endearing smiles from many around him. “These trains represent a landmark in the history of this great city, and indeed in the progress of transport technology generally.”

When quizzed on the line itself, he professes: “For too long some of the busiest and most populated parts of London have missed out on a tube service most of us take for granted. This is a policy which has been overlooked by London local assemblies since the creation of the tube network for financial reasons, which is preposterous; the Tower line will enable over a million Londoners to get to work and provide a much needed boost to the local economy of some of London's poorest boroughs.”

On the term “the Black Line”, he is characteristically candid and comical; “This term is a silly one, born of some fanatical concept that I have somehow brought darkness upon us by moving a cemetery.” The middle-eastern man shakes his head vigorously. Journalists laugh and press the issue of the cemetery.

“Believe me, if there was any way unearthing and relocating the burials at St. Peter ad Vincula could have been avoided we would certainly have done so. Our office spent two years in discussion to try to find alternatives to the strategy, but it was found that extending Tower Hill west was not only the most cost-effective, but logistically the only way we could realistically ensure the line was able to link into towns we so desperately wanted to connect it with.” He isn't quite so candid when asked how much money certain Premier League football clubs had been compelled to contribute to the project, and what part this factor had played in influencing that 'desperation' at achieving these connections, choosing instead to ignore the question.

Finally, satisfied that he has given adequately proportionate time to all of the journalists, Mayor Boris is ushered into the patiently waiting train.

Before he steps in, however, he is instinctively drawn, innately occupied by the man in the long black coat once more. Portentously it begins to rain at that very moment, and the aged man dons his hood, adding further sinister mysticism to his already troubling aura. Unblinking, he gazes expressionlessly at Mayor Boris, who this time is unable to avoid catching every word. The oration attracts his attention, like a magnet, and he cannot look away.

“You have released the tortured souls of the most brutal men ever to walk the Earth. Cast deep by St. Peter, their twisted sickness will find its way out from beneath the bed of the Thames, where you will send millions. You, Mayor.” He points an accusing finger, orange with the stains of nicotine, the nails chewed to destruction.

Mayor Boris, transfixed, is gently shunted onto the train by his staff, but still cannot tear away his gaze, his face now as jaundice as the mop of hair framing it. Before the doors slide shut, he hears the bearded man remark: “You have infected us all.”

The station attendant raises his baton to signal the train's departure. But he does so not to a person, but to a closed circuit camera on the train's roof. For Mayor Boris has another reason to celebrate – another landmark and flagship policy worked so hard to implement: this train has no driver.

Dusk is thickening rapidly now.

SUNDAY 8.00pm

TOWER LINE CONTROL CENTRE – TOWER HILL

The train's occupants are being watched.

Before Ranjit sits a large control panel, comprising of dials indicating speed, air-brake pressure, temperature and more. An imposing plan of the Tower line is on the wall before him, intermittently dotted with trios of bulbs; red, amber and green. Presently, most of the green lights are illuminated.

Ranjit focuses his attention on the eight screens directly before him at eye level. One of them is dedicated to tuning into CCTV platform activity from the train's roof, another exclusively devoted to the view ahead from the front of the train, via its “nose-cam”. The remaining screens each monitor activity within one of the train's six carriages, switching views periodically.

To amuse himself, alone in the office, Ranjit manually controls the closed circuit images from the train's only currently occupied carriage, zooming in on the five-man party of t.v. crew, the mop-headed man they are clearly continuing to interview (though Ranjit does not have the benefit of sound), and his two aides who look like accountants but probably know Kung-Fu.

“Good evening gentlemen, and you Boris you mad old nutter,” Ranjit chuckles to himself. “Welcome to the maiden voyage of the Black Line – sorry Boris, the Tower line.

“We're currently cruising at an altitude of zero feet, and our speed is a steady...” He glances at the digital speedometer before him, “...sixteen miles per hour. We'll be calling at Edmonton, Tottenham, Dalston, Stoke Newington, Peckham, Thornton Heath, and all the other black areas – sorry; culturally represented areas between here and Croydon.”

Ranjit glances across to the screen monitoring the track ahead, seeing a green light in the distance as the tunnel approaches, and looks up to cross-check this against the illuminated green bulb at the corresponding point on the wall-plan. Turning a large dial in the dead centre of the console anti-clockwise, he very slightly reduces the train's speed.

A large colleague appears behind him in the doorway, holding two steaming TfL mugs, one of which he places before Ranjit. Without looking up, the younger man thanks him.

“All going well?” enquires Ricardo, in a strong London accent which seems to defy his exotic monicker.

Ranjit nods. “Just going underground.” He continues to monitor ahead of the train as it passes the signal on its station approach, and enters the dark tunnel on a slight decline.

Ricardo, his supervisor, grins as he watches Mayor Boris mouthing silently to the television crew. He doesn't know why this amuses him – watching the mayor just seems to have this effect on the general public. “Boris,” he says, without objective, though not inaccurately. He blurted an identical thing once on the streets of north London, when he spied the mayor enjoying one of his trademark cycle rides, and was rewarded with a passing expressionless wave.

“Come on,” Ranjit is muttering to himself, “where's the bird? Come on love.”

Immediately on cue the soft, well-spoken female voice of the Underground permeates the train and the digitally adjoined office system; “The next station is Bush Hill Park.”

“Well done love.” Ranjit watches the light in the approaching distance through the nose-cam, now deep in the tunnel, as the train reaches its first stop on the Tower line, cross-checking it against the wall-plan for the imminent illumination of a red bulb. As the train passes a luminous sensor on the tunnel wall, a single monotone beep alerts him to the speedometer, which starts to independently reduce its value, further confirmed by a sizeable liquid crystal display above it, advising: “Automatic braking applied”.

“Congratulations Boris, it works,” says Ranjit. “You get to keep your job.”

……..

COPYRIGHT – 2011 MATT McAVOY

This represents a FREE SAMPLE of “THE BLACK LINE” by Matt McAvoy.

Please close this window to purchase the story in full, which is also published in “MODERN TALES OF HORROR – COMPLETE COLLECTION (The Black Line; Clouds; Granjy’s Eyes)”, by the same author.

In : My Work